The “IGWG Members Take the Mic” blog series intends to highlight lessons learned and best practices from and innovative approaches to gender transformative programming and research from IGWG members’ work and advocacy efforts to advance gender equality outcomes in global health. This blog is the first installment in this series. Read the second and final blog in the series on community backlash in male engagement programming here.

This blog post was developed in collaboration with the Agency for All project and authored by:

Courtney McLarnon (MEL Advisor), Center on Gender Equity and Health, University of California San Diego, USA, cmclarnon@health.ucsd.edu

Dinah Amongin (Lecturer), Makerere University, Uganda, damongin@musph.ac.ug

Lotus McDougal (Director of Gender Data and Methods), Center on Gender Equity and Health, University of California San Diego, USA, lmcdougal@health.ucsd.edu

Madeleine Short Fabic (Deputy Director, Health Division of the Bureau for Africa), United States Agency for International Development, USA, mshort@usaid.gov

The negative, gender-regressive consequences of infertility and related stigma are profound.

[He will be] insulting her, calling her names like ‘you dog’ or ‘you are very stupid.’ There is no need for him to keep her, and she has to leave.”1

[People] will not respect [a man who does not have a child]. They will call him by his first name.”2

Globally, one in six people has experienced some form of infertility[i] in their lifetime.3 Of all regions, sub-Saharan Africa bears the greatest burden of period infertility,4[ii] likely tied to higher rates of pregnancy-related complications and untreated sexually transmitted infections.5 Individuals and couples with infertility face immense stigma, as well as increased levels of stress, depressive episodes, loneliness, social isolation,6 marital dissolution, intimate partner violence,7 and economic distress.8

The stigma associated with infertility can negatively impact communities by affecting the environment in which people make decisions affecting their sexual and reproductive health.9 Stigma can create and reinforce contexts where individuals and couples take actions to avoid being perceived as infertile, contributing to health-related behaviors such as early marriage and childbearing, short birth spacing, and limited contraceptive use.10 Gendered stigma enforces norms and expectations influencing individuals’ lives, shaping their interactions, opportunities, and self-perceptions in gender-specific ways.

Despite these consequences, infertility-related experiences and stigma in sub-Saharan Africa are rarely studied or addressed, leading to a limited context-specific evidence base to inform policy and programming. This gap is contrary to broader sexual and reproductive health goals to support individuals in deciding whether, when, and with whom to have children. It also limits our understanding of how harmful gender norms and practices are influenced, perpetuated, or reinforced by infertility and related stigma. Without this understanding, infertility and infertility-related issues remain unaddressed, sexual and reproductive health suffers, and gender inequality persists.

Agency for All Is Building the Evidence Base in Cameroon and Kenya

Agency for All is a five-year project funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) that is working to generate evidence on the role of agency in social and behavior change programming to improve health and well-being. Recognizing the geographic burden of infertility in sub-Saharan Africa, and the profoundly gendered and normative consequences, Agency for All is conducting foundational research to understand the factors influencing infertility-related stigma in Cameroon and Kenya. This research is designed to inform interventions and provide new learnings that bring attention to and action on a long-neglected concern.

To inform this work, Agency for All conducted a literature review to explore myths and misperceptions, social consequences, and crosscutting factors associated with reproductive agency and infertility, as well as to identify promising, infertility-related social and behavior change and gender transformative programs11[iii] from across sub-Saharan Africa and globally. Infertility impacts people of all gender identities; however, the findings we synthesize are limited to cisgender and heterosexual women and men due to the focus of the existing literature. This blog shares insights from our review, highlighting key results and recommending next steps for gender transformative research, programming, advocacy, and policy on infertility.

Five Insights From a Literature Review in Sub-Saharan Africa

Infertility is a complex medical and public health issue that affects individuals, couples, families, and communities. It is influenced by environmental, social, and political systems, as well as basic access to services. The consequences of infertility and related stigma are profoundly gendered in their manifestations across sub-Saharan Africa. Women bear a disproportionate share of the burden,12 while men and individuals of other gender identities are often overlooked in research and programming. Here’s what we’ve learned so far:

- Infertility harms individuals and couples. Individuals with infertility often have compromised psychosocial well-being, including higher risk of stress, depressive symptoms,13 loneliness, sadness, social isolation, and suicidal thoughts and a lower quality of life.14 Couples experiencing infertility may face social and familial pressure to have extramarital affairs, become polygamous,15 or end their marriage, a phenomenon experienced by both women16 and men17 and sometimes openly endorsed18 by the broader community.

- Cultural beliefs about infertility impede reproductive agency. Socially constructed beliefs about the causes of infertility are common across different contexts in sub-Saharan Africa. Many of these beliefs, such as perceived promiscuity, inform norms that influence women’s behaviors and choices, including the use of modern contraceptives.19 Studies document widespread perceptions that infertility is a common side effect of using modern contraceptives,20 contributing to lower levels of use,21 particularly among young and newly married women who experience cultural pressures to demonstrate fertility. These misperceptions compromise women’s ability to set and achieve their own reproductive goals by limiting the choices they can make without risking social consequences.

- Infertility stigma reinforces inequitable gender norms. The practice of holding women responsible for infertility is well documented in research from sub-Saharan Africa.22 Infertility is often perceived as a female inadequacy; a woman who is unable to have children is seen as a failure in her role as a wife,23 whereas few studies in sub-Saharan Africa focus on men’s experiences of infertility. This blame can spur gender-based violence, in which women experience targeted physical or verbal abuse.24 It can also carry over into human rights violations; in some settings, fear of infertility has been used to promote female genital mutilation/cutting as a “cure.”25

- Infertility concerns contribute to child marriage and adolescent childbearing. Social norms and societal expectations pressure couples—especially women—to bear children upon marriage/union26 and further marginalize men from the discourse on fertility issues. High social value on childbearing in sub-Saharan Africa27 creates pressure to prove fertility at an early age in some countries, and early marriage and childbirth are recognized pathways to demonstrate fertility.28 Gendered stigma toward women is further compounded by son preference in some African countries, where not having a male child is considered equivalent to being infertile.29

- Policy-level attention to infertility issues is limited. The health policy landscape on infertility in sub-Saharan Africa is mixed, and evidence is sparse. There is little documentation of government programming that supports funding for and awareness of infertility.30 Sexual and reproductive health services in sub-Saharan Africa do not include biomedical infertility treatment services within public health financing or strategy. Assisted reproductive technologies, such as in vitro fertilization, are available in many countries, but are centralized in urban areas, are expensive, and are sometimes unregulated.31 Issues of affordability and access to treatment raise significant concerns related to intersectional factors of discrimination.

The Potential of Gender Transformative Interventions

There is growing evidence that interventions that support individuals and couples experiencing infertility can have profound impact on reducing stigma and building better outcomes.32 Such interventions include cognitive behavioral therapy, peer support groups, and mass media and social media approaches that build psychosocial and resilience assets and spread awareness. Increased investment in developing and testing innovative approaches to improving experiences around infertility should include education, counseling, and stigma-reduction activities that build on evidence from successful fertility awareness33 and norms-shifting programming.34

Gender transformative social and behavior change interventions that address the psychological and social determinants and consequences of infertility can bring significant value to individuals and couples in sub-Saharan Africa by challenging and transforming unequal gender norms, roles, and power dynamics that contribute to stigma, blame, and discrimination. For example, our literature review concluded that there is limited awareness of the challenges faced by men with infertility, perpetuating the perception that infertility is a women’s issue and compounding stigma. Interventions should be explicit about gender discrepancies in infertility experiences and incorporate notions of gender equity, agency, empowerment, and autonomy.

Interventions that aim to promote equitable fertility-related decision-making, shared responsibilities, improved communication between partners, and supportive environments for seeking care have growing potential. Examples of gender transformative approaches from initiatives in low- and middle-income countries include:

- Infertility testing and services for men35 to reduce infertility-related gender discrimination.

- Educational programs36 that provide accurate information on fertility, contraception, and reproductive health and rights for everyone in the community and initiatives that engage men in infertility discussions and encourage them to seek health and support services.

- Individual and couple-based counseling services37 that address gendered attitudes, roles, and stigma toward people experiencing infertility.

- While evidence is growing, structural efforts38 including policy and advocacy efforts to challenge harmful gender norms and stigma, hold great promise. Such efforts would likely have greater impact were they to adopt an intersectional lens in support of individuals, couples, and communities in all their diversity.

Where Do We Go From Here?

To date, infertility has not been a priority in global sexual and reproductive health research and programming. It has yet to be prioritized in programming in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa—from policy to research to implementation—where the social consequences of infertility are high and where stigma has a sweeping, negative impact. Results from our literature review highlight the importance of recognizing and addressing infertility as a common, highly stigmatizing, gendered, and long-neglected concern.

We encourage the broader global health community to sharpen the focus on reproductive empowerment by giving deserved attention to infertility and the ways in which infertility-related stigma manifests and inhibits reproductive and relational agency and individual well-being. We are not alone in our sentiment; in April 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO) released infertility prevalence estimates alongside policy and programmatic recommendations. Considering the results of our review and the emerging WHO recommendations, we recommend the following actions for governments, funders, researchers, program implementers, and others whose work touches on infertility:

- Invest in context-specific formative research to understand the unique gender-related drivers of infertility-related stigma and the broader social and economic impacts to inform responsive strategies, services, policies, and interventions. This research can highlight long-neglected intersectional issues around infertility, including stigma and treatment access, and how such issues influence other attitudes and behaviors, such as child and forced marriage, adolescent birth, contraceptive uptake, female genital mutilation/cutting, and intimate partner violence. Formative research can also identify potential strategies for early diagnosis and treatment and structural interventions to address policy, practice, and societal factors that underlie infertility stigma and discrimination. This research should include a focus on men’s experiences of infertility to contribute to destigmatizing infertility.

- Design and implement gender transformative interventions that aim for structural change at the policy and advocacy levels, increase community awareness, address stigma, and support individuals and couples to achieve their self-determined reproductive goals.

- Increase the availability and accessibility of infertility testing and treatment, especially for those who have been precluded from accessing such services due to cost and other barriers. Receiving a diagnosis, even without access to treatment, can alleviate suffering for individuals and couples. This suggests that education, consultation, and low-cost diagnostic examinations could be a first step to providing care—and a potential investment area for the research and development community.

- Prioritize funding for sexual and reproductive health policies and programs at the national and subnational levels to improve equity of access to and quality of comprehensive reproductive health care that encompasses the prevention, detection, and treatment of infertility for all.

Our literature review was the first step to inform upcoming formative research, which we hope will fill some of these gaps. We encourage others to help fill the void so we can improve understanding and awareness; address urgent treatment gaps; and promote gender norms, policies, and behaviors that reduce and ultimately end infertility-related stigma and discrimination and improve sexual and reproductive health.

The Agency for All team invites readers to read the full review here.

This publication is made possible by the generous support of USAID under cooperative agreement 7200AA22CA00023. This post was produced and prepared independently by the authors. The contents of this post are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

Endnotes

[i] Infertility is defined by the World Health Organization as a disease of the male or female reproductive system characterized by the failure to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse. Lifetime infertility refers to the occurrence of this failure to achieve a pregnancy over the course of an individual’s lifetime. Period infertility refers to the occurrence of this failure to achieve a pregnancy over the course of a given time interval—in this case, 12 months.

[ii] Sub-Saharan Africa bears the highest burden of period infertility, but not lifetime infertility, a data paradox most likely explained by the dearth of studies measuring lifetime infertility in the region.

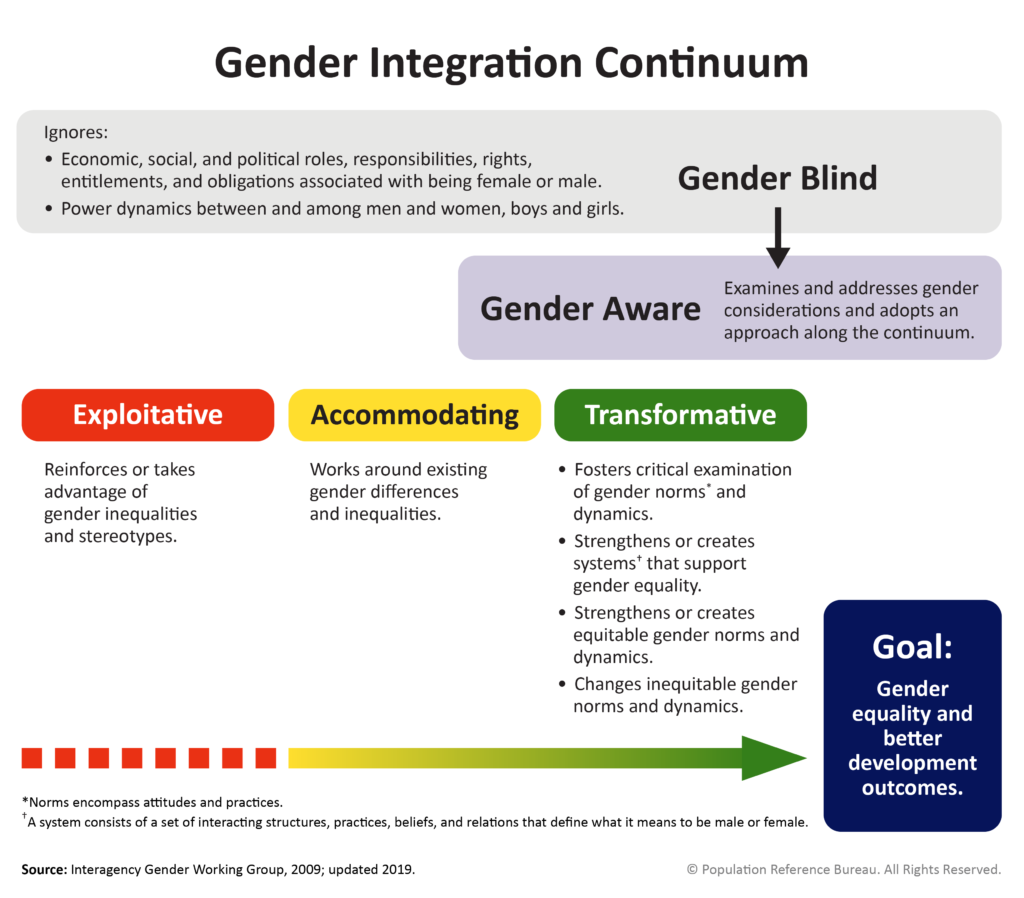

[iii] Transformative policies and programs seek to transform gender relations to promote equality and achieve program objectives. This approach attempts to promote gender equality by 1) fostering critical examination of inequalities and gender roles, norms, and dynamics; 2) recognizing and strengthening positive norms that support equality and an enabling environment; 3) promoting the relative position of women, girls, and marginalized groups; and 4) transforming the underlying social structures, policies, and broadly held social norms that perpetuate gender inequalities.

References

- Bornstein, M., J. D. Gipson, G. Failing, V. Banda, and A. Norris. 2020. “Individual and Community-Level Impact of Infertility-Related Stigma in Malawi.” Social Science & Medicine 251: 112910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112910. ↩︎

- Bornstein, Gipson, Failing, Banda, and Norris, “Individual and Community-Level Impact of Infertility-Related Stigma in Malawi,” 112910. ↩︎

- World Health Organization. 2023. Infertility Prevalence Estimates, 1990–2021. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978920068315. ↩︎

- World Health Organization, Infertility Prevalence Estimates, 1990–2021. ↩︎

- World Health Organization, Infertility Prevalence Estimates, 1990–2021. ↩︎

- Cui, W. 2010. “Mother or Nothing: The Agony of Infertility.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 88(12): 881-2. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.10.011210. ↩︎

- Hess, R.F., R. Ross, and J.L. Gililland. 2018. “Infertility, Psychological Distress, and Coping Strategies Among Women in Mali, West Africa: A Mixed-Methods Study.” African Journal of Reproductive Health / La Revue Africaine de La Santé Reproductive 22(1): 60–72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26493901. ↩︎

- Anaman-Torgbor, J.A., J.W.A. Jonathan, L. Asare, B. Osarfo, R. Attivor, et al. 2021. “Experiences of Women Undergoing Assisted Reproductive Technology in Ghana: A Qualitative Analysis of Their Experiences.” PLOS One 16(8): e0255957. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255957. ↩︎

- Bornstein, Gipson, Failing, Banda, and Norris, “Individual and Community-Level Impact of Infertility-Related Stigma in Malawi,” 112910. ↩︎

- Bornstein, Gipson, Failing, Banda, and Norris, “Individual and Community-Level Impact of Infertility-Related Stigma in Malawi,” 112910. ↩︎

- Interagency Gender Working Group (IGWG). 2017. The Gender Integration Continuum Training Session User’s Guide. ↩︎

- Fledderjohann, J.J. 2012. “‘Zero is Not Good for Me’: Implications of Infertility in Ghana.” Human Reproduction 27(5): 1383–90. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/des035. ↩︎

- Groene, E.A., C. Mutabuzi, D. Chinunje, E.M. Shango, S. Kulasingam, et al. 2021. “Comparing Infertility-Related Stress in High Fertility and Low Fertility Countries.” Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare (29): 100653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2021.100653. ↩︎

- Olusola, P.A., O.D. Olaogun, and T. Aduloju. 2018. “Quality of Life in Women of Reproductive Age: A Comparative Study of Infertile and Fertile Women in a Nigerian Tertiary Centre.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 38(2): 247-251. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2017.1347916. ↩︎

- Cui, “Mother or Nothing: The Agony of Infertility,” 881-2. ↩︎

- Ofosu-Budu, D. and V. Hanninen. 2020. “Living as an Infertile Woman: The Case of Southern and Northern Ghana.” Reproductive Health 17(69). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00920-z. ↩︎

- Dierickx, S., K.O. Oruko, E. Clarke, S. Ceesay, A. Pacey, et al. 2021. “Men and Infertility in the Gambia: Limited Biomedical Knowledge and Awareness Discourage Male Involvement and Exacerbate Gender-Based Impacts of Infertility.” PLOS One 16(11): e0260084. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260084. ↩︎

- Bornstein, M., S. Huber-Krum, M. Kaloga, and A. Norris. 2021. “Messages Around Contraceptive Use and Implications in Rural Malawi.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 23(8): 1126-41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2020.1764625. ↩︎

- Bornstein, Gipson, Failing, Banda, and Norris, “Individual and Community-Level Impact of Infertility-Related Stigma in Malawi,” 112910. ↩︎

- Bell, S.O., C. Karp, C. Moreau, and A. Gemmill. 2023. “If I Use Family Planning, I May Have Trouble Getting Pregnant Next Time I Want to”: A Multicountry Survey-Based Exploration of Perceived Contraceptive-Induced Fertility Impairment and Its Relationship to Contraceptive Behaviors.” Contraception: X (5): 100093, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conx.2023.100093. ↩︎

- Sedlander, E., J.B. Bingenheimer, S. Lahiri, M. Thiongo, P. Gichangi, et al. 2021. “Does the Belief That Contraceptive Use Causes Infertility Actually Affect Use? Findings from a Social Network Study in Kenya.” Studies in Family Planning 52: 343-59. https://doi.org/10.1111/sifp.12157. ↩︎

- Dimka, R.A. and S.L. Dein. 2013. “The Work of a Woman Is to Give Birth to Children: Cultural Constructions of Infertility in Nigeria.” African Journal of Reproductive Health / La Revue Africaine de La Santé Reproductive 17(2): 102–17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23485925. ↩︎

- Fledderjohann, “‘Zero is Not Good for Me’: Implications of Infertility in Ghana,” 1383–90. ↩︎

- Dhont, N., J. Van de Wijgert, G. Coene, A. Gasarabwe, and M. Temmerman. 2011. “‘Mama and Papa Nothing’: Living With Infertility Among an Urban Population in Kigali, Rwanda.” Human Reproduction (26)3: 623–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deq373. ↩︎

- Tabong, P.T.N. and P.B. Adongo. 2013. “Understanding the Social Meaning of Infertility and Childbearing: A Qualitative Study of the Perception of Childbearing and Childlessness in Northern Ghana.” PLOS One 8(1): e54429. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0054429. ↩︎

- Bornstein, Gipson, Failing, Banda, and Norris, “Individual and Community-Level Impact of Infertility-Related Stigma in Malawi,” 112910. ↩︎

- Cui, “Mother or Nothing: The Agony of Infertility,” 881-2. ↩︎

- Bornstein, M., J. D. Gipson, G. Failing, V. Banda, and A. Norris. 2020. “Individual and Community-Level Impact of Infertility-Related Stigma in Malawi.” Social Science & Medicine 251: 112910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112910. ↩︎

- Beyeza-Kashesy, J., S. Neema, A.M. Ekstrom, F. Kaharuza, F. Mirembe, et al. 2010. “‘Not a Boy, Not a Child’: A Qualitative Study on Young People’s Views on Childbearing in Uganda.” African Journal of Reproductive Health (14)1: 71-81. https://www.ajrh.info/index.php/ajrh/article/view/475. ↩︎

- Beyeza-Kashesy, Neema, Ekstrom, Kaharuza, Mirembe, et al., “‘Not a Boy, Not a Child’: A Qualitative Study on Young People’s Views on Childbearing in Uganda,” 71-81. ↩︎

- Anaman-Torgbor, Jonathan, Asare, Osarfo, Attivor, et al, “Experiences of Women Undergoing Assisted Reproductive Technology in Ghana: A Qualitative Analysis of Their Experiences,” e0255957. ↩︎

- Gerrits, T., H. Kroes, S. Russell, and F. van Rooij. 2023. “Breaking the Silence Around Infertility: A Scoping Review of Interventions Addressing Infertility-Related Gendered Stigmatisation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 31(1): 2134629. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2022.2134629. ↩︎

- Institute for Reproductive Health (IRH). 2023. “FACT Project’s WALAN Group Learning and Counseling Model.” https://www.irh.org/walan-group-learning-counseling/. ↩︎

- High Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). 2022. Social Norms: Promoting Community Support for Family Planning. Washington, DC: USAID. https://www.fphighimpactpractices.org/briefs/social-norms/. ↩︎

- Inhorn, M.C. and P. Patrizio. 2015. “Infertility Around the Globe: New Thinking on Gender, Reproductive Technologies and Global Movements in the 21st Century.” Human Reproduction Update 21(4): 411-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmv016. ↩︎

- Naab, F., R. Brown, and E.C. Ward. 2021; “Culturally Adapted Depression Intervention to Manage Depression Among Women With Infertility in Ghana.” Journal of Health Psychology 26(7): 949-61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319857175. ↩︎

- Ehsan, Z., M. Yazdkhasti, M. Rahimzadeh, M. Ataee, and S. Esmaelzadeh-Saeieh. 2019. “Effects of Group Counseling on Stress and Gender-Role Attitudes in Infertile Women: A Clinical Trial.” Journal of Reproduction & Infertility 20(3): 169–77. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31423420/. ↩︎

- Gerrits, Kroes, Russel, van Rooji, “Breaking the Silence Around Infertility: A Scoping Review of Interventions Addressing Infertility-Related Gendered Stigmatisation in Low- and Middle-Income Countries.”, 2134629. ↩︎